I have recently “thought led” on LinkedIn, claiming that the future of software development lies in mob programming. I think this take automatically flips my bozo bit in the minds of certain listeners, whilst for many people that is a statement about as revolutionary as saying water is wet.

Some definitions (based on my vague recollection and lazy googling to verify, please let me know if you know better) about what I mean by mob and pair programming.

Solo development

This is what you think it is. Not usually completely alone in the dark wearing a hoodie like in the films, but at least, you sit at your own screen, pick up a ticket, write your code, open a PR, tag your mates to review it, get a coffee, go through and see if there are PRs from other developers for you to review. Rinse / repeat.

The benefit here is you get to have your own keyboard shortcuts , your own Spotify playlist and can respond immediately to chat messages from the boss. The downside is that regulators don’t trust developers, not alone, so you need someone else to check your work. We used to have a silo for testers, but like trying to season the food afterwards, it is impossible to retrofit quality, so we have modified our ways of working, but the queue of pull requests in a review queue is still a bottleneck, and if you are unlucky, you lose the “race” and need to resolve merge conflicts before your changes can be applied to the trunk of the source tree.

Pair programming

Origins

Pair programming is one of the OG practices of Extreme Programming (XP), developed in 1996 by Kent Beck, Ward Cunningham and Ron Jeffries, and later publicised in the book Extreme Programming Explained (Beck) and basically means one computer, two programmers. One person types – drives – the other navigates. It makes it easier to retain context in the minds of both people, it is easier to retain state in case you get interrupted, and you spread knowledge incredibly quickly. There are limitations of course, if the navigator is disengaged or if the two people have strong egos and you get unproductive discussions over syntactic preference, but that would have played out in pull requests/code review anyway, so at least this is resolved live. In practical terms this is rarely a problem.

Having two people work on code is much more efficient than reviewing after the fact, but it is of course not completely guaranteed, but it is pretty close. The only time I have worked in a development team that produced literally zero defects, pair programming was mandatory, change sets were small, and releases were frequent. We recruited a pair of developers that had already adopted these practices at a previous job, and in passing chat with some of our developers ahead of joining they had mentioned that their teams had zero defects, and our people laughed – because surely that’s impossible. Then they showed us. Test first, pair program, release often. It works. There were still occasions where we had missed a requirement, but that was discovered before code went live, but still of course led us to evolve our ways of working until that didn’t happen either.

Downsides?

The most obvious naive observation would be 2 developers, one computer – surely you get half the output? Now, typing speed is not the bottleneck when it comes to software development, but more importantly – code has no intrinsic value. The value is in the software delivering the right features at the least possible investment of time and money (whether it is creation or maintenance), so writing the right code – including writing only code that differentiates your business from the competition – is a lot more important than writing the most code. Most people in the industry are aware of this simple fact, so generally the “efficiency loss” of having two people operating one computer is understood to outweigh by delivering the right code faster.

On the human level, initially people rarely love having a backseat driver when coding, either you are self-conscious about your typing speed or your rate of typos or you feel like you are slowing people down, but by frequently revolving pairs and roles driver/navigator the ice breaks quickly. You need to have a situation where a junior feels safe to challenge the choices of a senior, i.e. psychological safety, but that is generally true of an innovative and efficient workplace, so if you don’t have that – start there. Another niggle is that I am still looking for a way to do it frictionlessly online. It is doable over Teams, but it isn’t ideal. I have had very limited success with the collab feature in VS Code and Visual Studio, but if it works for you – great!

Overall

People that have given it a proper go seem to almost universally agree on the benefits, even if that began as a thing forced upon them by an engineering manager, seem to appreciate it. It does take a lot of mental effort, because the normal breaks to think as you type get skipped because your navigator is completely on it, so you write the whole time, and similarly the navigator can keep the whole problem in mind and does not have to deal with browsing file trees or triggering compilations and test runs, they can focus on the next thing. All in all this means that after about 6-7 hours, you are done. Just give up, finish off the day writing documentation, reporting time, do other admin and check emails – because thinking about code will have ceased. By this time in the afternoon you will probably have pushed a piece of code into production, so it’s also a fantastic opportunity to get a snack and pat yourself on the back as the monitoring is all green and everything is working.

Mob programming

Origins

In 2011, a software development team at Hunter Industries happens upon Mob Programming as the evolution from practicing TDD and Coding Dojos and applying those techniques to get up to speed on a project that had been put on hold for several months. A gradual evolution of practices, as well as a daily inspection and adaptation cycle, resulted in the approach that is now known as Mob Programming.

2014 Woody Zuill originally described Mob Programming in an Experience Report at Agile2014 based on the experiences of his team at Hunter Industries.

Mob programming is next level Pair Programming. Fundamentally, the team is seated together in one area. One person writes code at the time, usually projected or connected into a massive TV for everyone to be able to see. Other computers are available for research, looking at logs or databases, but everyone stays in the room, both physically and mentally, so everybody doesn’t get to sit at a table with their own laptop open, the focus is on the big screen. People talk out loud and guide the work forward. Communication is direct.

Downsides

I mean it is hard to go tell a manager that a whole team needs to book a conference room or secluded collaboration area and hang all day, every day going forward – it seems like a ludicrously expensive meeting, and you want to expense a incredibly large flatscreen TV as well – are the Euros coming up or what? Let me guess you want Sky Sports with that? All joking aside, the optics can be problematic, just like it would be problematic getting developers multiple big monitors back in the day. At some companies you have to let your back problems become debilitating before you are allowed to create discord by getting a fancier chair than the rest of the populace, so – those dynamics can play in as well.

The same problems of fatigue from being on 100% of the time can appear in a mob and because there are more people involved, the complexities grow. Making sure the whole team buys in ahead of time is crucial, it is not something that can be successfully imposed from above. However, again, people that have tried it properly seem to agree on its benefits. A possible compromise can be to pair on tickets, but code review in a mob.

Overall

The big leap in productivity here lies in the the advent of AI. If you can mob on code design and construction, you can avoid reviewing massive PRs, evade ensuing complex merge conflicts and instead safely deliver features often. The help of AI agents. yet with a team of expert humans still in the loop. I am convinced a mob approach to AI-assisted software development is going to be a game changer.

Whole-team approach – origins?

The book The Mythical Man-Month came out in 1975, a fantastic year, and addresses a lot of mistakes round managing teamwork. Most famously the book shows how and why adding new team members to speed up development actually slows things down. The thing I was fascinated by when I read it was essay 3, The Surgical Team. A proposal by Harlan Mills was something akin to a team of surgeons with multiple specialised roles doing work together. Remember at the time Brooks was collating the ideas in this book, CPU time was absurdly expensive, terminals were not yet a thing, so you wrote code on paper and handed it off to be hole punched before you handed that stack off to an operator. Technicians wore a white coat when they went on site to service a mainframe so that people took them seriously. The archetypal java developer in cargo shorts, t-shirt and a beard was far away still, at least from Europe.

The idea was basically to move from private art to public practice, and was founded on having a a team of specialists that all worked together:

- a surgeon, Mills calls him a chief programmer – basically the most senior developer

- a copilot, basically a chief programmer in waiting, basically acts as sounding board

- an administrator – room bookings, wages, holidays, HR [..]

- an editor – technical writer that ensures all documentation is readable and discoverable

- two secretaries that handle all communication from the team

- a program clerk – a secretary that understands code, and can organise the work product, i.e. manages the output files and basically does versioning as well as keeps notes and records of recent runs – again, this was pre-git, pre CI.

- the toolsmith – basically maintains all the utilities the surgeon needs to do his or her job

- the tester – classic QA

- the language lawyer – basically a Staff Programmer that evaluates new techniques in spikes and comes back with new viable ways of working. This was intended as a shared role where one LL could serve multiple surgeons.

So – why was I fascinated, this is clear lunacy – you think – who has secretaries anymore?! Yes, clearly several of these roles have been usurped by tooling, such as the secretaries, the program clerk and the editor (unfortunately, I’d love having access to a proper technical writer). Parts of the Administrator’s job is sometimes handled by delivery leads, and few developers have to line manage as it is seen as a separate skill. Although it still happens, it is not a requirement for a senior developer, but rather a role that a developer adopts in addition to their existing role as a form of personal development.

No, I liked the way the concept accepts that you need multiple flavours of people to make a good unit of software construction.

The idea of a Chief Programmer in a team is clearly unfit for a world where CPU time is peanuts compared to human time and programmers themselves are cheap as chips compared to surgeons, and the siloing effect of having only two people in a team understand the whole system is undesirable.

But, in the actual act of software development, having one person behind the keyboard, and a group of people behind them constantly thinking about different aspects of the problem being solved, they each have their own niche and they can propose good tests to add, risks to consider as well as suitable mitigations – I think from a future where a lot of the typing is done by an AI agent – the concept really has legs. The potential for quick feedback and immediate help is perfect and the disseminated context across the whole team lets you remain productive even if the occasional team member goes on leave for a few days. The obvious differences in technical context aside, it seems there was an embryo there for what has through repeated experimentation and analysis developed into Mob Programming of today.

So what is the bottleneck then?

I keep writing that typing speed is not the bottleneck, so what is? Why is everything so bad out there?

Fundamentally code is text. Back in the day you would write huge files of text and struggle to not overwrite each other’s changes. Eventually, code versioning came along, and you could “check out” code like a library, and then only you could check that file back in. This was unsustainable when people went on annual leave and forgot to check their code back in, and eventually tooling improved to support merging code files automatically with some success.

In some organisations you would have one team working the next version of a piece of software, and another team working on the current version being live. At the end of a year long development cycle it would be time to spend a month integrating the new version into the various fixes that had been done to the old version over the whole year of teams working full time. Unless you have been involved in something like that, you cannot imagine how hard that is to do. Long lived branches become a problem way before you hit a year, a couple of days is enough to make you question your life choices. And, the time spent on integration is of literally zero value to the business. All you are doing is shoehorning changes already written in order to get the new version in a state where it can be released, that whole month of work is waste. Not to mention the colossal load on testing it is to verify a year’s worth of features before going live.

People came up with Continuous Integration, where you agree to continuously integrate your changes into a common area making sure that the source code is releaseable and correct at all times. In practice this means you don’t get to have a branch live longer than a day, you have to merge your changes to the agreed integration area every day.

Now, CI – like Behaviour Driven Development has come to mean a tool. That is, do we use continuous integration? Yeah, we have Azure DevOps, the same way BDD has become we use SpecSharp for acceptance tests, but I believe it is important to understand what words really mean. I loathe the work involved in setting up a good grammar for a set of cucumber tests in the true sense of the word, but I love giving tests names that adhere to the BDD style, and I find that testers can understand what the tests do even if they are in C# instead of English.

The point is, activities like the integration of long lived branches and code reviews of large PRs become more difficult just due to their size, and if you need to do any manual verification, working on a huge change set is inherently exponentially more difficult than dealing with smaller change sets.

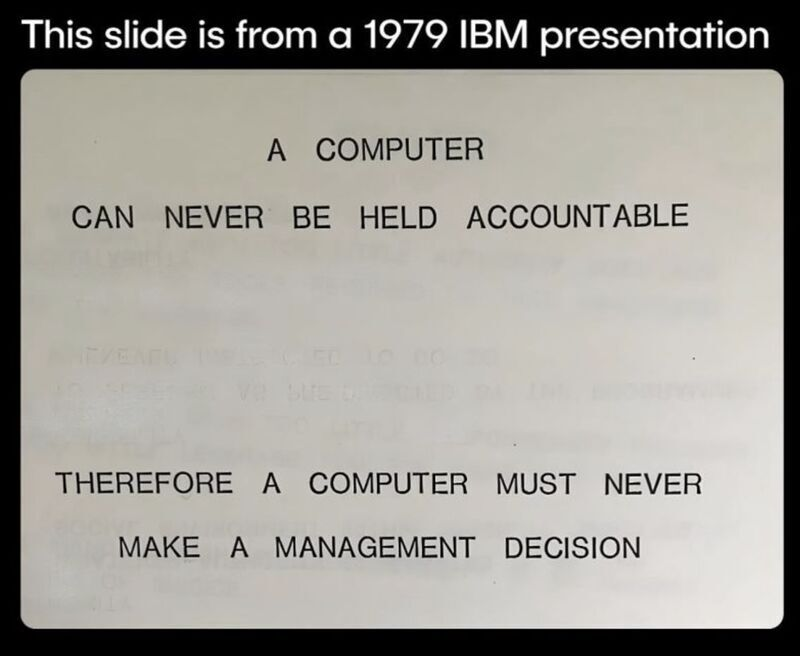

But what about the world of AI? I believe the future will consist of programmers herding AI agents doing a lot of the actual typing and prototyping, and regulators deeply worried about what this means for accountability and auditability.

The solution from legislators seem to be Human-in-the-Loop, and the only way to avoid the pitfalls of large change sets whilst giving the business the execution speed they have heard AI owes them, is to modify our ways of working so that the output of a mob of programmers can be equated to reviewed code – because, let’s face it – it has been reviewed by a whole team of people – and regulators worry about singular rogue employees being able to push malicious code into production, so if anything, if an evildoer wants to bribe developers, rather than needing to bribe two, they would now have to bribe a whole team without getting exposed, so I think it holds up well from a security perspective. Technically of course, pushes would still need to be signed off by multiple people for there to be accountability on record and to prevent malware from wreaking havoc, but that is a rather simple variation on existing workflows, the thing we are trying to avoid is an actual PR review queue holding up work, especially since reviewing a massive PR is what humans do the worst at.

Is this going to be straightforward? No, probably not, as with anything, we need to inspect and adapt – carefully observe what works and what does not, but I am fairly certain that the most highly productive teams of the future will have a workflow that incorporates a substantial share of mob programming.